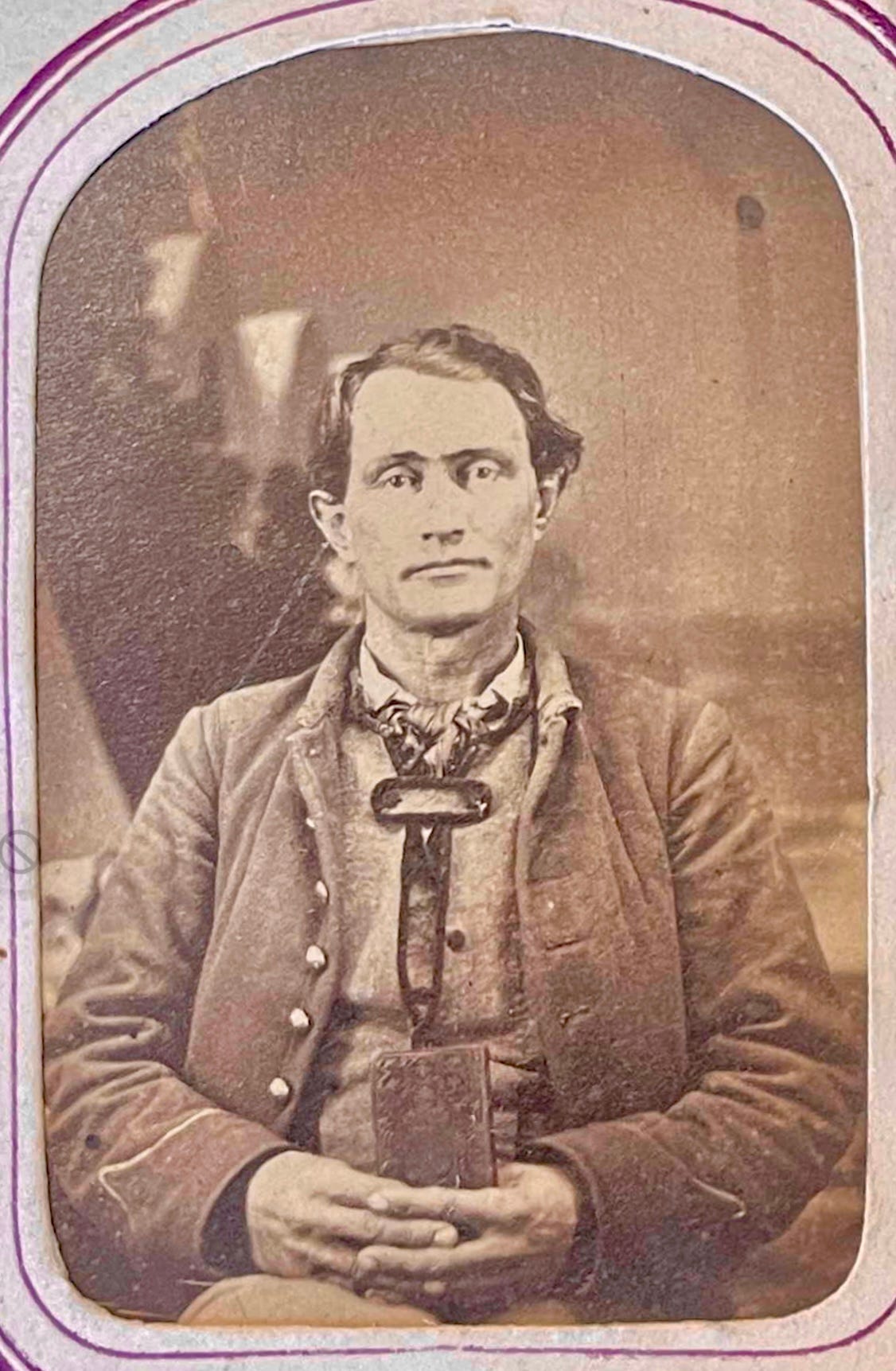

From Civil War Captain to Christian Church Minister: Part 1

… the unlikely journey of Benjamin Franklin Northcutt (1820-1895).

#237. Postmark September 20, 1966. Addressed Mrs. B.D. Superior, WI

Tuesday a.m. 8 o’clock

Dear Penny,

I’ve just had my hymn sing. My good Baptist friends call a hymn singing session a ‘sung-spiration’ and I think that is a good name. I ended up with “Work, for the night is Coming”. I’ve known that as long as I’ve known anything. I just play through the book the ones I like as they come. Yesterday I had “I hear thy welcome voice“ and I think of my grandfather*, standing up leading the singing when there was no one else to do it – then it was without an organ and grandfather didn’t even have a pitch pipe, but he could sing – how I love to reminisce!

We are evidently having our equinox weather – the drizzle began Sunday afternoon and all day yesterday it continued – sometimes rained quite hard – the weather reports had clearing by noon. And I think before long the sun is coming out. I hope so. I’m to go to Knox to visit with an old friend.

Aunt Nell called me yesterday. She certainly has perked up within the last few months – she really sounded cheerful when she talked. I am going on the bus and will probably come home that way – not too long a day but by 3:20 I’m about ready to rest a bit. I’m glad to spend dark days away, not trying to see anything requiring close vision. Yesterday afternoon after my rest, I cut out some sewing. I need badly a dark wash dress. I went to town one day last week and bought the material and now it is cut and ready to stitch when the sun shines. I also cut out a little three year-old a birthday dress and because she has a little sister, I cut her one also. I don’t particularly care for dresses alike, but like grandma Moses said about painting blue sky on several canvases at the same time “it saves paint“ so it saves a little material – but also there was only one piece of material with a small figure. Speaking of eyes. I hope your contact lenses work. I didn’t think your glasses detracted from your appearance, but if you feel better without glasses, well you’ll feel better without them, and as I told Bertha Cruz when she had her ears pinned back. I thought those ears were cute, but she was always conscious of them.

I’m glad you were doing a little Saturday morning substituting. You’ll learn to know the children in your church and through them eventually the parents. I’m always happy at anything that makes you happy, including your husband and little children.

I love you, OOOOXXXX Grandmother

[May Emma Northcutt Hinkson]

* May’s grandfather was Benjamin Franklin Northcutt (1820-1895), who is my 3x great-grandfather.

As I read through my great-grandmother May’s weekly letters in chronological order, 1966 is the first year that I have both letters that May wrote to her daughter Helen (my grandmother) and Penny (my mother). It’s interesting to me to read and compare the letter’s contents to the two different family members, often written the same day or just one day apart. The letters to my grandmother Helen contain more details about LaBelle friends and residents than the letters to my mother, Penny, do. In Penny’s letters she tended to do a bit more reflection and reminiscing. Occasionally, she would also allow herself to offer her granddaughter advice. The letter noted above includes a nice memory of my great-grandmother’s own grandfather, Benjamin Franklin Northcutt (1820-1895). In his later adult years, B.F. Northcutt was a minister for the First Christian Church who according to his bio “was well-known and admired for his piety and religious zeal”. But before taking up the pulpit, he had been a farmer and a Civil War Captain.

Benjamin Franklin Northcutt (1820-1895) was a farmer, father to six children, and 41 years of age when he accepted the leadership position of Captain for the Antioch Company of the Northeast Missouri Home Guards in 1861.

The Northeast Home Guards were a self-organized militia of Knox, Scotland, Adair, and Lewis County men who sided with the Union’s stance against slavery and the need for unification. I’m not sure what propelled him to join the militia when he had a wife and at least six children at home to support. But, I suspect in 1861 at the very start of the agitation between the unionists and secessionists, that neither Benjamin nor the 98 other Knox and Lewis County men that joined him had any idea how bad the conflict would become. The Home Guard was initially created as a militia-like force to defend local communities. They were not intended for extended military duty nor large scale battles.

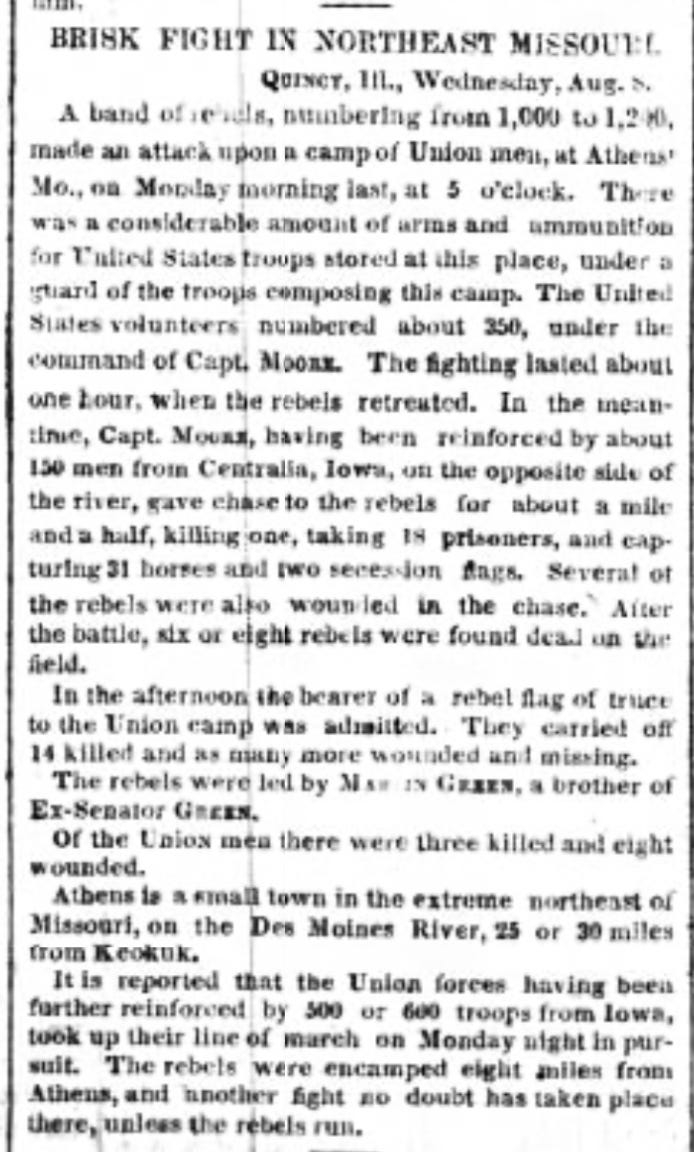

Knox County in the 1860s had been mostly Union-sympathetic. However, the northeast counties of Missouri also had a significant number of pro-South secessionists. The secessionists had been agitating things for several months when in the summer of 1861 they organized themselves under the leadership of Col. Martin Green (brother to the then-current Missouri Senator James Green). Around this time, they began to more strongly assert themselves throughout Northeast Missouri, especially around the towns of Athens, Millport, and Edina. This unsettling situation occurred very near the small Colony community, where Benjamin Northcutt and his family lived.

The first major conflict involving the newly formed Northeast Missouri Home Guards occurred on July 30, 1861. The secessionists under Green’s command marched on Edina, MO (18 miles from Colony) and overwhelmed the Home Guard, and then assumed occupation of the town. Within a week, on August 5, 1861, the Secessionists would move farther north to engage the Missouri Home Guard at Athens, along the Missouri-Iowa border.

Under the command of Colonel David Moore, the Missouri Home Guard would achieve a decided victory for the Unionists at Athens, where they were outnumbered three-to-one. The Home Guard, armed with newly acquired Springfield rifled muskets, defeated Green and his more than 1,000 men. This stopped the conflict from crossing the river into Iowa. The Battle of Athens has the distinction of being the northernmost Civil War battle west of the Mississippi River.

I can’t imagine how it must have felt to my 3x great-grandfather Benjamin to experience this kind of fighting for the first time. As the Captain, he would have been instrumental in leading his Company. And while I’m sure he experienced quite a bit of angst in leading his men, any concern he may have had was most likely heightened by the fact that his teenage son was also a volunteer Home Guard.

News about the Athen’s military engagement traveled quickly throughout the country, even making the front page of the New York Times:

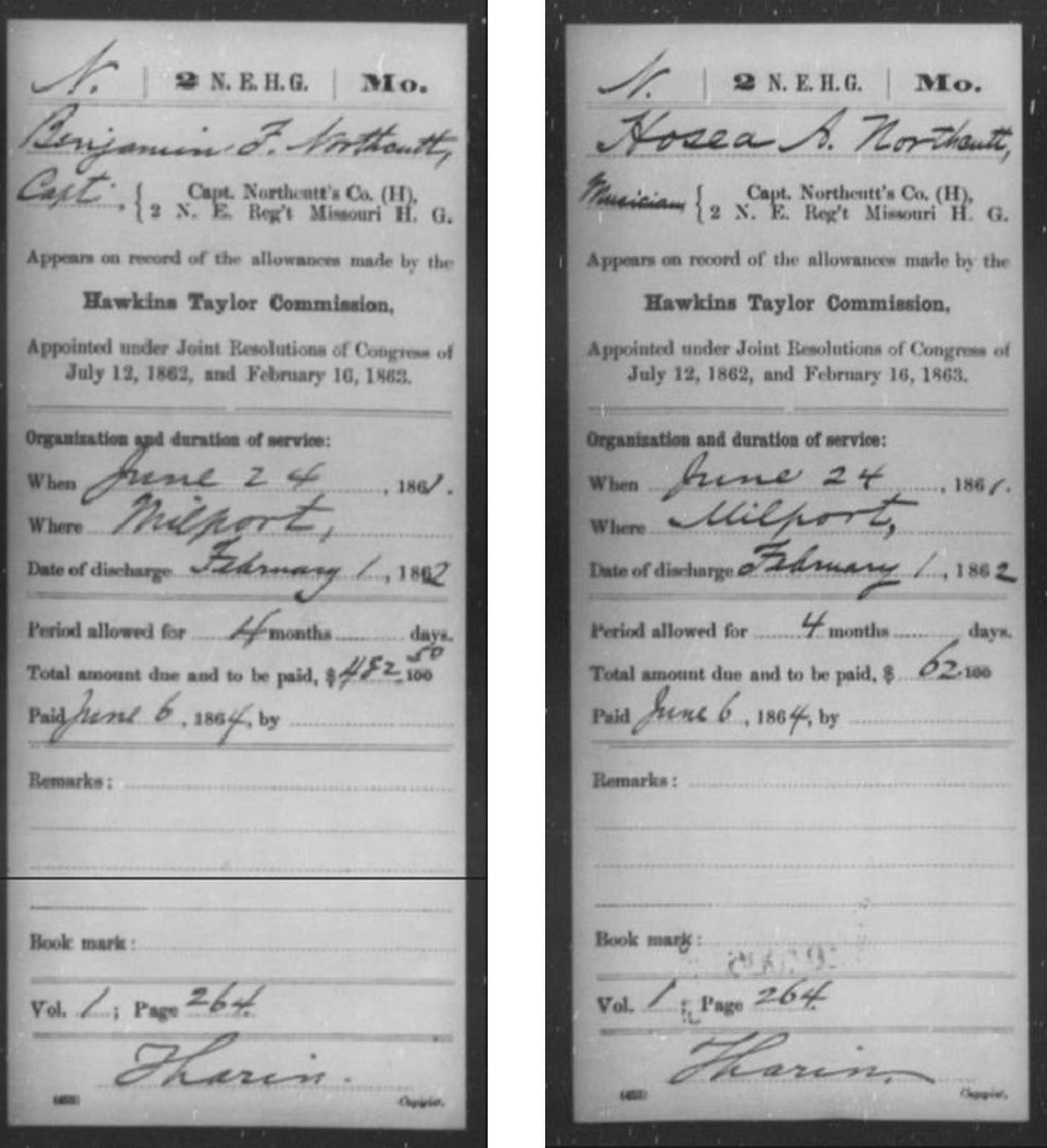

Hosea Allen Northcutt (1843-1907) was only sixteen years old when he joined the Home Guard under his father’s command. His service records show that he enlisted on June 24, 1861, on the same day as his father. His rank, though, was not that of a private. Instead, he was noted as being a “musician.”

The service cards for Benjamin and Hosea are interesting in several respects. Not only do they show rank and dates of service, but they also indicate the amount of payment for service rendered during the war. Although the Northeast Missouri Home Guard was a volunteer militia, Congress, under the direction of Abraham Lincoln, established a commission in 1862 to evaluate and determine proper payment to Missouri soldiers who had remained loyal to the Union during the Civil War. Known as the Hawkins Taylor Commission (Hawkins Taylor was a political ally of Lincoln’s), it was specifically set up to acknowledge the contributions of the all-volunteer Missouri Home Guard at the start of the war. Without the Home Guards' early contributions to the Union’s effort, the state of Missouri would have most likely become a Confederate stronghold. The state was very much divided in both politics and volunteer militias. While the Missouri Home Guards supported Union efforts, the Missouri’s volunteer State Guards were pro-South secessionists.

Hosea’s designation as a “Musician” is especially interesting to me. During the Civil War, young recruits were often enlisted as buglers or drummers to support communication on the battlefield. Bugle calls and drum patterns were used to convey specific orders, such as "Charge," "Retreat," or "Assemble.” They helped ensure that troops understood commands even amidst the noise of battle.

I’m not sure if it was Hosea’s idea to join the Home Guard as a musician, but I suspect that it was most likely the opposite. Hosea, as a young man of sixteen, was probably more interested in trying to prove himself in battle. His father, I’m sure, had other ideas. Perhaps he had concerns about his firstborn son joining the Home Guard. Or, if he did not, perhaps he was appeasing the pleas of his wife, Lydia Jane Northcutt, whom I sure would have been concerned about young Hosea’s involvement in the militia.

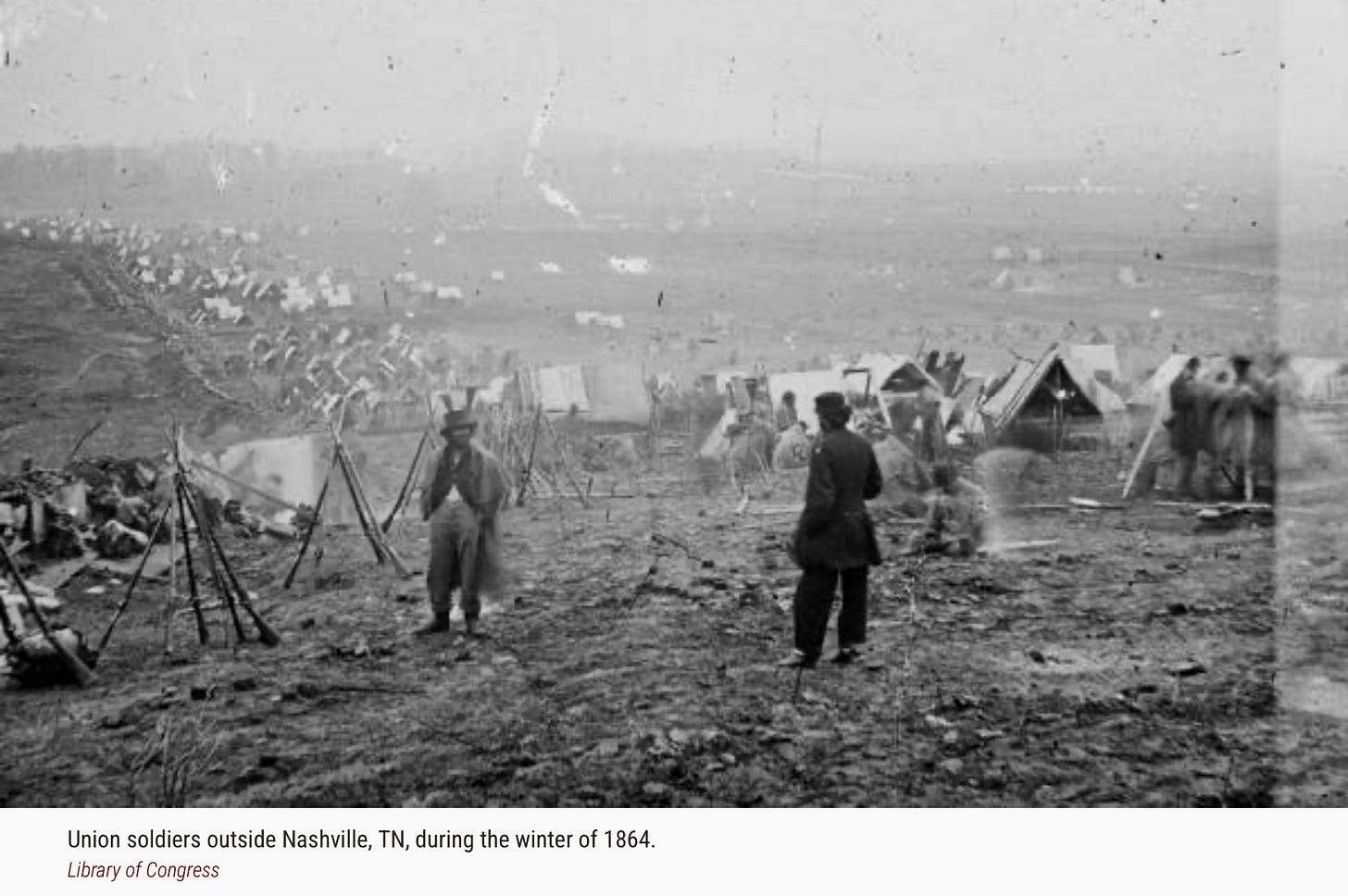

This photo of the Missouri Home Guards is unidentified. But I can’t help wondering if it might be Captain Northcutt’s Company, especially when I look at the age of the young drummer on the left.

The 2nd Northeast Missouri Home Guard participated in several other skirmishes throughout the fall of 1861. By December, it was clear that enthusiasm among the volunteers of both the 1st and 2nd companies of the Home Guards was waning. In February, the two volunteer regiments were disbanded and combined to form the 21st Missouri Infantry of the Union Army. On Feb 12, 1862, over 900 men from both Home Guard regiments were ‘mustered in’ at Canton, MO.

This summary provides an overview of the Northeast Home Guards’ formation and accomplishments.

From what I can gather, neither Benjamin Franklin Northcutt nor his son Hosea joined the other Home Guards who were mustered into the 21st Missouri Infantry. I suspect that seven months of service as Home Guards were enough for both father and son, especially after fighting against other Missourians (perhaps even some of their neighbors). The Taylor Hawkins Commission issued payment on June 4, 1862, to both father and son for their service. B. F. Northcutt was paid $482.50 (~$14,626 in 2025 dollars) for an estimated four months' service as Captain of the 2nd Northeast Home Guards. Hosea Allen Northcutt would earn $62 (~$1,962 in 2025 dollars) for his service as the company’s musician.

While it seemed for a while that both Northcutt men were to escape further Civil War involvement, things would change after Congress enacted the very first national draft.

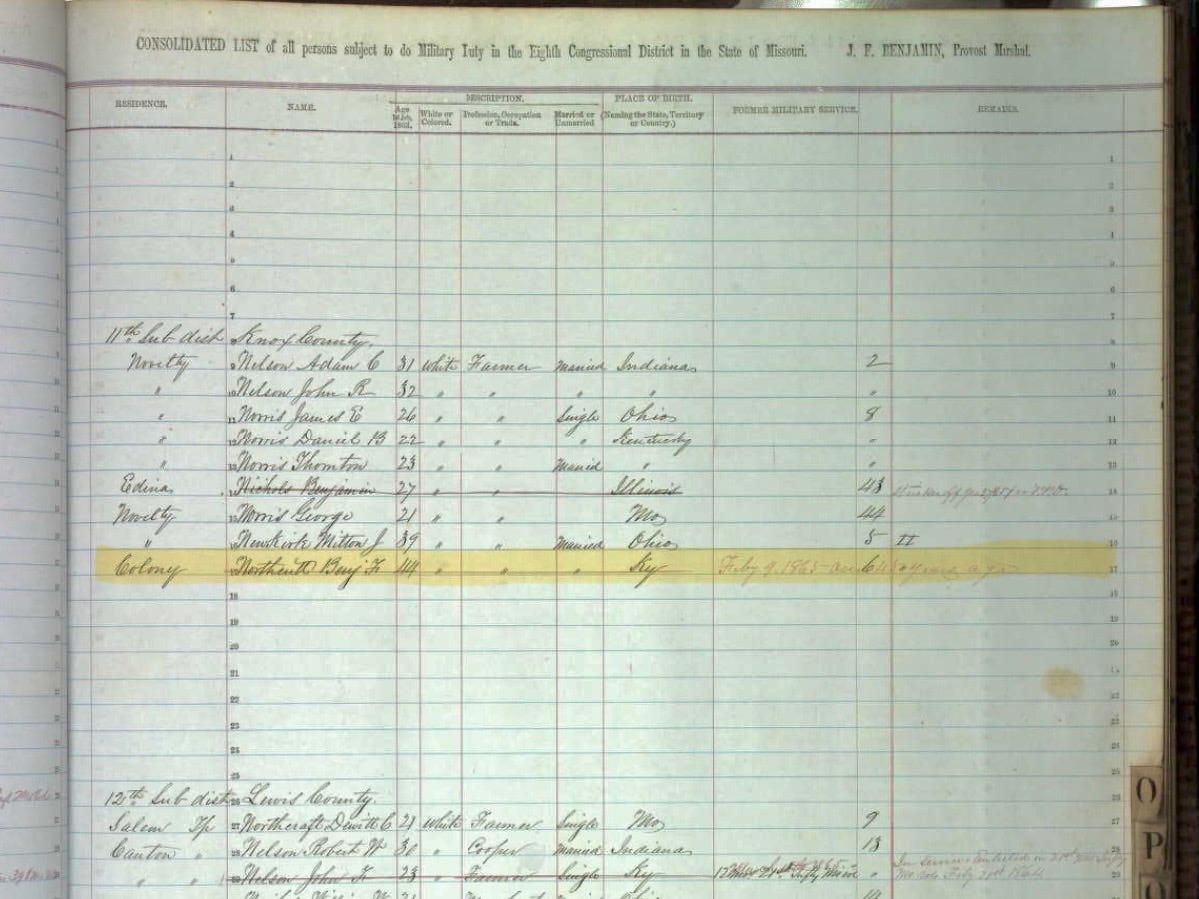

The Enrollment Act of 1863 was the first instance of a national draft in US history. It mandated registration for military service for all male citizens between 20 and 45 years old. Since B.F. Northcutt was 43 years of age, he registered. But, fortunately for Hosea, his 20th birthday was still eight months away at the time of the Congressional Act’s passing. His name was not recorded when his father registered, nor was it ever added later. I assume that this was because procedures were not yet in place when he finally turned twenty.

I can only speculate on the events that led B.F. to voluntarily enlist less than a year later on March 31, 1864. There is no known family story about his enlistment nor any documentation about his motivation or reasoning. What I do know is that at the time, there were three different ways a recruit could be enlisted into the war: conscription, voluntary enlistment, or through a third process known as Substitute voluntary enlistment. This last option enabled another volunteer to serve in place of a drafted individual. Each of these three methods involved the signing of a different official agreement. The Substitute Voluntary agreement (view example) was distinctly different from the Voluntary Enlistment agreement. It frequently involved some form of monetary compensation from the draftee to the substitute for taking on the drafted individual's term of service.

For quite some time, I have pondered and contemplated the question as to why my 3x great-grandfather would have voluntarily enlisted. The question that I keep coming back to is why he would have volunteered when he had a) already stepped away from the conflict after his service as Captain in the Missouri Home Guards and b) he was less than a year away from aging out of war service eligibility at the age of 45. In all my research and pondering of this question, I keep coming to the same conclusion… I believe the driving reason that Benjamin F. Northcutt voluntarily enlisted in the Missouri Infantry was to keep his oldest son, Hosea, out of serving in the war.

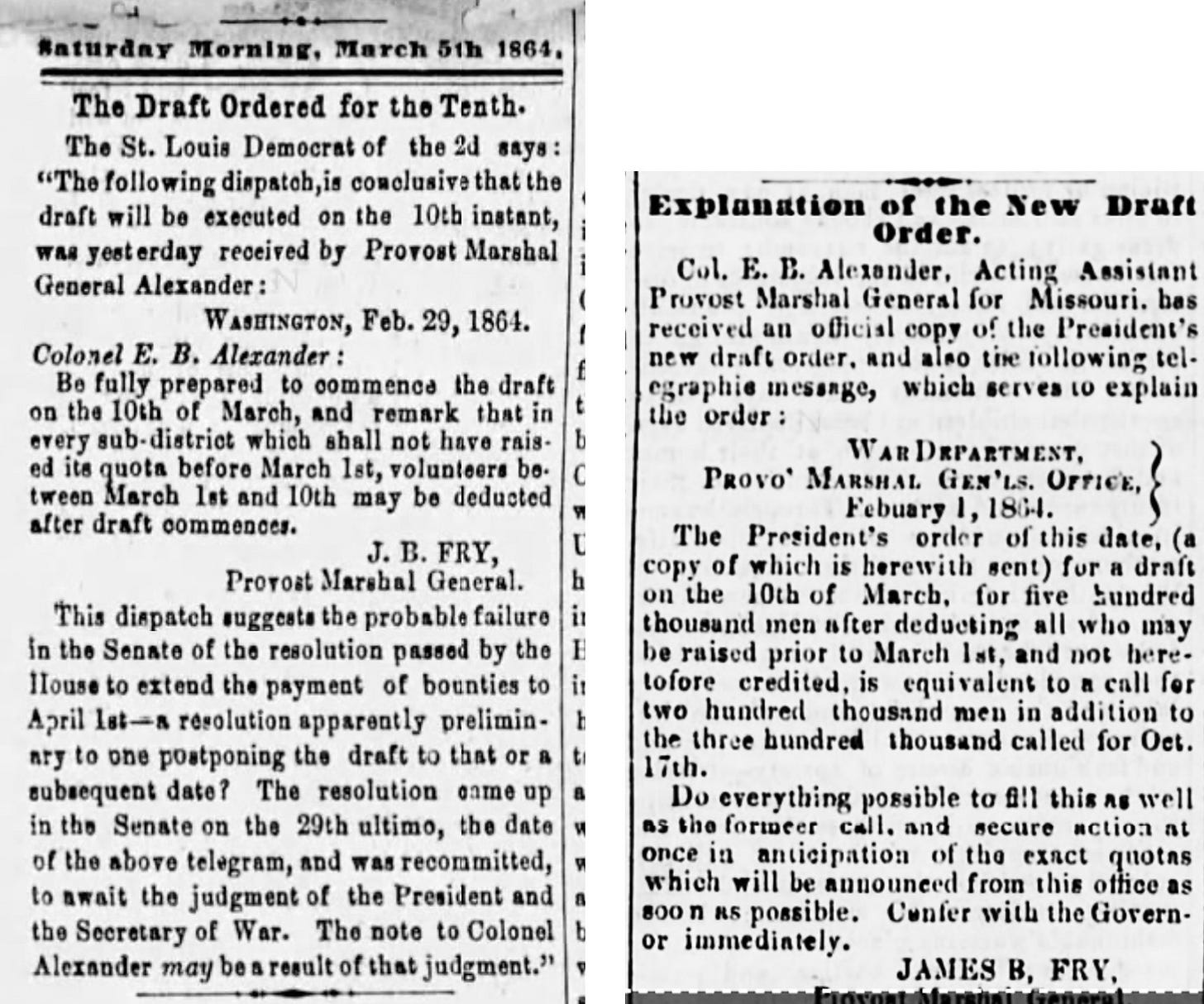

By the winter of 1863, it had become evident that Missouri would most likely be forced to utilize the draft as early as March 1864. In spite of a $100 “bounty” reward, volunteer recruits had been running low, and those who had already enlisted were nearing the completion of their three-year service period. In Knox and Lewis counties, word about the pending draft had been well publicized. With enrollment quotas established for each county, strong patriotic messages were used to appeal to citizens to voluntarily fill the ranks rather than by conscripted draft.

Benjamin F. Northcutt was, I’m sure, well aware of this pressure. He wouldn’t have been able to travel into town without seeing pending draft notices posted. News items filled the front pages of the newspapers. Word of the pending draft and enlistment quotas was everywhere. These notices from the Lewis County newspaper communicated the quota for the March 1864 draft of 200,000 new men. Initially, the deadline date for the draft was set for March 10, but it was extended to April 1st to provide time for communities to try and meet their quotas by voluntary enlistment.

On the last day of the voluntary enlistment period, the Canton Press-News published the enlistment progress for all the counties in the 8th Missouri District. Only Scotland county, the county in which the Battle of Athens had occurred, met its quota through voluntary recruits. Knox County, the county that B.F. Northcutt lived in, was only 4 enlistments away from their quota.

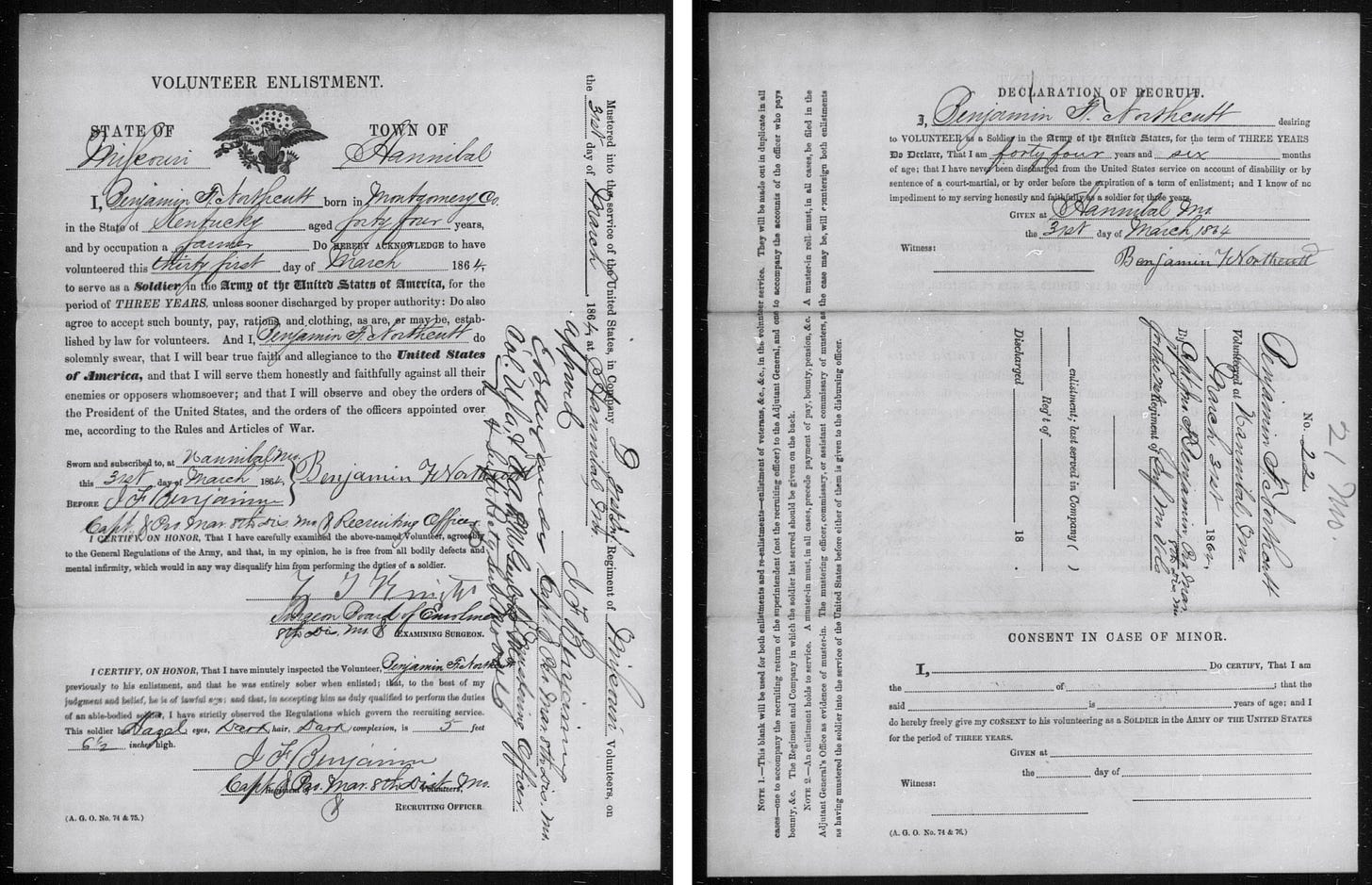

B.F. Northcutt was among the recruits who volunteered the last day of the pre-draft enlistment period on March 31, 1864. He was 44 years and 6 months old when he voluntarily joined the 21st Missouri Infantry. The Volunteer Enlistment form below bears his signature on both the front and back of the document.

I suspect that B.F. may have privately brokered some type of deal with a local official to keep Hosea’s name off the draft list. I can only imagine the conversations that my 3x great-grandparents, Benjamin and Lydia, may have had and the anguish they may have felt over such a decision. On one hand, I’m sure they both had a strong desire to protect their oldest son from potential harm. On the other hand, they knew that B.F.’s enlistment to the Missouri Infantry would mean the family would be without a patriarch and that the risks were high of him never returning home.

The war records for Benjamin’s service in the 21st Missouri Infantry can be found here. (5 images) and here (19 images). Here are two cards that show his enlistment date and a summary of absences from his regiment.

His records indicate that he had at least seven medical absences during his 14 months of service before the war ended in June 1865. He was in and out of several military hospitals, mostly battling sickness. This was not unusual. Diseases and infections caused by unsanitary conditions, poor hygiene, and substandard diets were a constant risk, even among the best provisioned regiments.

The American Civil War represents a landmark in military and medical history as the last large-scale conflict fought without knowledge of the germ theory of disease. Unsound hygiene, dietary deficiencies, and battle wounds set the stage for epidemic infection, while inadequate information about disease causation greatly hampered disease prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Pneumonia, typhoid, diarrhea/dysentery, and malaria were the predominant illnesses. Altogether, two-thirds of the approximately 660,000 deaths of soldiers were caused by uncontrolled infectious diseases, and epidemics played a major role in halting several major campaigns. These delays, coming at a crucial point early in the war, prolonged the fighting by as much as 2 years. (Sartin JS. Infectious diseases during the Civil War: the triumph of the "Third Army". Clin Infect Dis. 1993 Apr;16(4):580-4. doi: 10.1093/clind/16.4.580. PMID: 8513069.)

Between June 1864 and May 1865, Benjamin spent considerable time in and out of the sick wards in several makeshift military hospitals. According to his muster roll call records (completed every two months), he was admitted to hospitals due to sickness at:

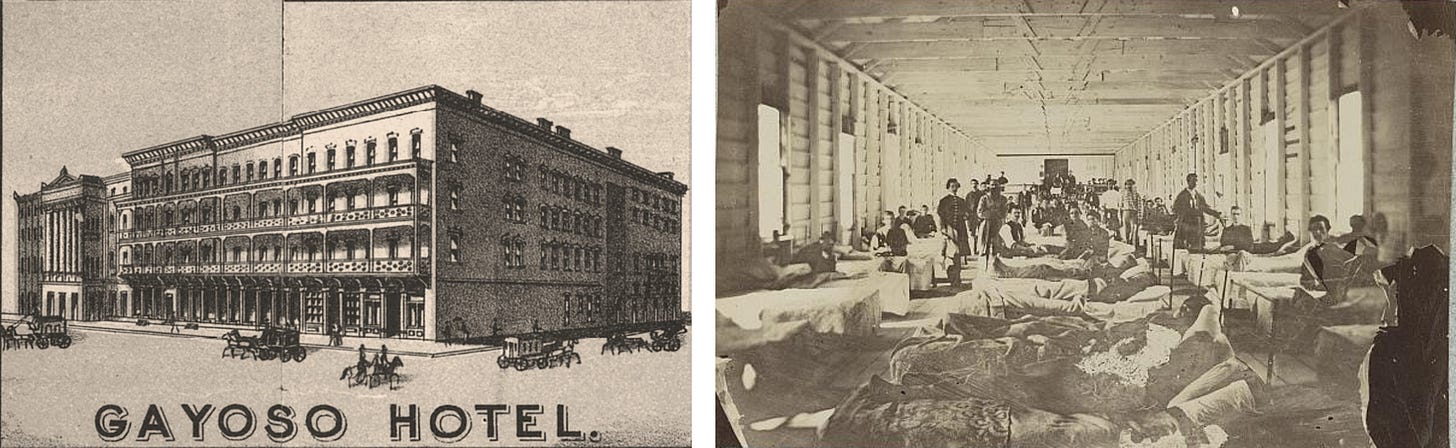

Memphis Gayoso (Hotel) Hospital on August 17, 1864. I’m not sure how long he was in, but it must have been just a short period for he was again out…

“Mound City” on Sept 12, 1864. Mound City, Illinois, served as a base for Naval activity up and down the Mississippi River. There was a large General hospital there that treated soldiers.

New Orleans, LA, hospital on March 16, 1865.

Baton Rouge, LA hospital on April 2, 1865

When the war ended in the spring of 1865, Benjamin’s regiment was located in Mobile, Alabama. The last large battle that his regiment was involved in was the Battle of Fort Blakeley (Alabama) took place April 2- 9, 1865. The battle resulted in a Confederate surrender, which would also coincidentally end the same day as Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

It looks like Benjamin may have fallen ill during the lead-up to this battle. His records show that he entered the hospital in Baton Rouge on April 2, just six days after the start of the siege of the Spanish Fort and Fort Blakeley (March 26 - April 9, 1861). But he was assuredly present for much of the regiment’s last three months of activities. This account from the 21st Missouri Regiment Infantry Veteran Volunteers: Historical Memoranda (published in July 1899) notes the regiment’s participation in the Battle and its final activities:

On the morning of the 17th of December, 1864, the 16th Corps, under Gen. A. J. Smith, was ordered in pursuit of Gen. Hood’s fleeing army. The pursuing army followed to Clifton, by way of Pulaski, and arrived at Clifton on the 2d of January. Here they embarked on board transports en route for Eastport, Miss., where they arrived on the 7th of January, 1865, and went into camp, remaining in camp and performing usual routine duty until February 9th, when they embarked on transports for New Orleans, where they landed on February 21st. They remained in New Orleans in camp until March 22d, when they took steamer and were carried, by way of Lake Pontchartrain and the Gulf, to Dauphin Island, at the foot of Mobile Bay, where they camped, arriving on the 24th. A few days afterwards another move was made to Spanish Fort, near Mobile, via Fish river and a land march. The Fort was invested and captured on April 8th. On the 3d of April the division, in which was the 21st regiment, began operations against Fort Blakely, taking part in the many skirmishes in the approach and siege of that important Confederate stronghold, and in its final capture on April 9th. In the charge on the fortifications on the 9th, the 21st had two color bearers killed and was the first regiment to plant its flag on the ramparts. In the charge the loss of the regiment was heavy, about equal to that of the whole brigade.

We heard at Blakely the rumor of Lee’s surrender, during the afternoon of the charge and capture of the fort. The bugle sounded the charge at 6 o’clock p. m. and in seven and one-half minutes the fort surrendered. This was the last battle of the war. The Federal loss was two thousand killed and wounded. We captured thirty-two cannon and four thousand prisoners. Thus the 21st Missouri was engaged in the last battle of the war as well as in one of the first.

On April 13th the 21st Regiment marched with the 16th Corps to Montgomery, Alabama, arriving on the 27th and going into camp two miles northeast of the city. Here they remained in camp until June 1st, when they were taken, with the brigade, to Providence Landing, on the Alabama River, reaching there June 4th, and embarked on a steamer the same day for Mobile. On the arrival of the regiment at Mobile they went into camp in the suburbs. Here they remained, doing outpost and other guard duty until March, when they were ordered to Fort Morgan for duty, and on April 19th, 1866, were mustered out.

(The 21st Missouri Regiment Infantry Veteran Volunteers: Historical Memoranda, pg. 33-34, Published July 1899)

Although the Civil War technically ended on April 9, 1865, when Robert E. Lee surrendered his troops to Ulysses S. Grant at the Appomattox Court House in Virginia, it took a while for the official news to travel and for skirmishes in some areas to end. Benjamin Franklin Northcutt was released from duty and “mustered out” on June 5, 1865, after the regiment had reached Mobile. Most of the regiment remained intact for another year, overseeing peacekeeping and transition activities.

For Benjamin Franklin Northcutt, the end of the war could not have come sooner. He had thankfully survived his 14 months in the infantry by remaining injury-free and was able to recover from his many ailments. Many other enlisted men were not as lucky. According to National Park Civil War records, the 21st Missouri Infantry lost a total of 309 men during its time as a regiment; 70 men (2 officers, 68 enlisted) from mortal wounds, 239 (5 officers, 234 enlisted) from sickness, infection, and disease.

Like many men who returned from the war, it appears that Benjamin Franklin Northcutt was a changed man. Although I believe he had always been a God fearing and religious man, it seems that the war had not only made his faith stronger but also changed his priorities. Within the next few years, B.F. would sell off all his land, move his family to educate his children, and pursue the highest calling he could imagine… ministry in his Christian faith.

Closing Note: If you look at Benjamin Franklin Northcutt’s hands in the photo of him in his Union jacket at the start of this chapter, you’ll notice he’s holding a small Bible. A small foretell to his next chapter in life.

» Follow the rest of B.F. Northcutt’s story in Part 2.

» Follow the rest of B.F. Northcutt’s story in Part 2

What an interesting story! I'm really impressed with the amount and quality of the documentation you found. I'm looking forward to seeing more of this story.

What a story Lori. 16 is so young to go to war. I think of the 16 year old boys in my life, and I just can't imagine sending them off to war. My father's brother at age 15, put his age up to 18 to enlist in WW2. I see photos of that young fresh faced boy and can't imagine the authorities didn't know he was underage. Such was the the desperation for fit young bodies to send away to battle.